It's OK to Make Conservation Human-Centric

How Shifting Our Perspective of "Wilderness" Can Lead to a More Sustainable Relationship with the Environment

When we think about nature, we often imagine wild spaces untouched by human hands. It’s difficult to refute, at least for someone like me who was raised to “have dominion over the earth.” It helps to think of this concept in the same way as the “heavy traffic” problem—just as you aren’t “stuck in traffic” but are actually part of the traffic, we aren’t separate from nature; we are nature.

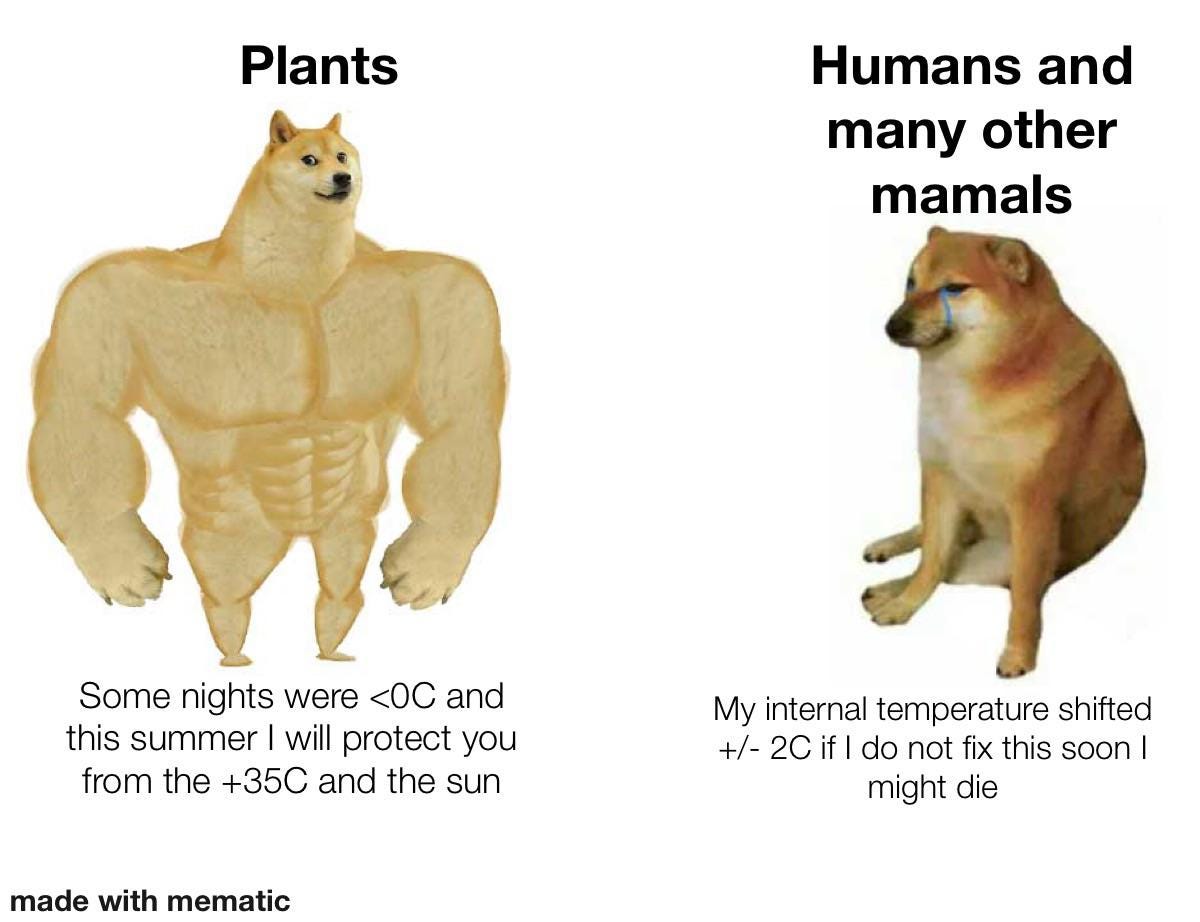

After all, humans evolved alongside everything else, with the same set of needs. Our actions, decisions, and lifestyles all contribute to the flow and balance of the natural world, just as each car on the road contributes to the traffic.

Humans have also been altering ecosystems throughout our history. This is not a bad thing, nor a good thing—just a thing we do very well! All living beings affect their environment to prioritize survival of their species; humans just have a much broader range of tolerance (hello, future Mars citizens!).

That being said, we’re still not the top survivors.

This behavior is the core of why and how ecosystems function. A functioning ecosystem is one where the components and processes work together, often in seemingly conflicting ways, to support life. Each species plays a role in the food web and nutrient cycling.

Balance is a Process, Not a Goal

The natural world is in a constant balancing process. We tend to oversimplify when we explain this, like saying “wolves are needed to control deer population.” These one-dimensional views make for a quick defense of wolves, but they gloss over the complexities of the wolf-deer relationship and the broader impacts of both species in their ecosystem.

In reality, every interaction within an ecosystem is part of a much larger web of influences, many of which are subtle and interconnected in ways we’re only beginning to understand. While it’s tempting to view ecosystems in simple terms, modern science has revealed a far more intricate reality—one that stretches beyond food webs and into the deepest realms of biology and even quantum biology1.

For those curious about how the smallest building blocks of life interact in this vast web of connections, I highly recommend reading The Sacred Depths of Nature by cell biologist Dr. Ursula Goodenough.

Whether you focus on quarks, cells, or mosquitos, my point is that we cannot possibly know the exact mechanisms of every bit of matter or energy around us. Each tiny piece contributes to the ultimate goal of survival of itself, its “parent” organism, etc.

These mysteries are overwhelming, and a lot of people sort of glaze over or outright ignore them. This is understandable, and another evolutionary survival tactic for energy conservation. Even if we don’t grasp every scientific detail, we can still make informed choices that support the ongoing balance of nature. After all, it’s this process of balancing that produces hurricanes and floods, or extreme heat and humidity—what we now understand as the effects of climate change.

The most effective step we can take is to promote biodiversity in our home habitats. We all make mistakes building our habitats, often without realizing them for years. Research shows the best way to mitigate these mistakes is through diversification—whether it’s the plants we cultivate, the animals we support, or the food we consume.

From the Ground to the Gut

On the extreme micro scale, I was surprised to learn our local ecosystems have measurable effects on health and may be contributing to a rise in chronic health disorders.

According to research compiled by Helene Wierzbicki, a fellow with the 2024 cohort of Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments (ANHE)2, there are two main biodiversity systems that play a vital role in keeping us healthy: one in our local environment and the other within our own bodies. The microbes that live in our airways, gut, and skin help regulate our immune systems and maintain balance. Research suggests that long-term exposure to diverse microbes in our environments strengthens our immune responses and reduces allergic reactions. This concept is tied to the “hygiene hypothesis,” which argues that over-sanitization in modern, Western societies disrupts our exposure to beneficial microorganisms, weakening our immune system.

In a related concept, the “biodiversity hypothesis” proposes that a reduction in plant variety has a direct impact on immune health, contributing to conditions like autoimmune diseases, cancer, and depression, all of which are linked to higher levels of inflammation in areas with less biodiversity. Studies from Finland show that children exposed to biodiverse environments are better equipped to prevent autoimmune disorders and allergies3.

This research highlights the interconnectedness between the natural world and our internal microbiota. The microbes found in healthy ecosystems also influence the microbial communities on our skin and within our bodies. When this relationship is disrupted, it can lead to immune system dysfunction. Supporting native plants and preserving biodiversity in our environment, therefore, plays a crucial role in fostering a diverse microbial landscape that benefits human health.

With documented benefits to human health and survival, why do we not work harder to preserve biodiversity around our homes? As someone with related chronic health issues, please consider this a personal plea.

Tips for Understanding How Humans Fit in Nature

Shift your mindset to see yourself as part of the natural world: Many of us have grown up thinking of humans and human homes as separate from nature. But we are deeply connected to and dependent on the ecosystems around us. By seeing ourselves as integral components of nature, we can better understand our responsibilities and roles in maintaining ecological balance.

Recognize that our daily decisions impact the local ecosystem: Because we are part of our local ecosystem, everything we do, from the products we bring into our habitat or the plants we allow to grow, affects the natural systems around us. These choices shape the local environment, influencing soil health and animal life, as well as air and water quality. By being mindful, we contribute to a healthier, more balanced ecosystem.

Aim for resilience, not stability: True balance in nature is dynamic, not static. Trying to maintain stability in a constantly changing world can lead to more harm than good. Instead, focusing on resilience—our ability to adapt and recover—will help us better weather changes, both in our environment and our societies. Our strength is in our tolerance range. To ensure the survival of humanity, we have to take measures to keep our ecosystem parameters within that range.

Remember that nature abhors a vacuum: When any part of an ecosystem is removed or damaged, nature will find a way to fill the gap—often with unintended consequences. Whether it’s invasive species taking over vacant niches in your garden or extreme weather events from atmospheric changes4, disruptions don’t go unnoticed. It’s a reminder that any of our actions can set off a chain reaction in the natural world.

As we recognize our role within human-focused ecosystems, we can take proactive steps to enhance local resilience and biodiversity. Planting native species, conserving water, and creating wildlife-friendly spaces are just a few ways we can make our homes and communities part of the solution, rather than part of the problem.

Brookes J. C. (2017). Quantum effects in biology: golden rule in enzymes, olfaction, photosynthesis and magnetodetection. Proceedings. Mathematical, physical, and engineering sciences, 473(2201), 20160822. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2016.0822

Wierzbicki, H. (2024) Mitigation of Chronic Health. https://wildones.org/tag/health/

Dunn, R. (2016, May). Letting Biodiversity Get Under Our Skin. Anthropocene. https://anthropocenemagazine.org/2016/05/letting-biodiversity-get-under-our-skin/

Poynting, M. and Stallard, E. (2024, June 17) How climate change worsens heatwaves, droughts, wildfires and floods. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-58073295